Ko Kirikirikatata kā mauka tapu

Ko Aoraki te mauka

Ko Waitaki te awa, ko whiti atu te Moananui a Kiwa, ki Korotuaheka

Ko Uruao te waka

Ko Rākaihautū te takata

Ko Waitaha te iwi

Descendants of Rākaihautū, our history flows through the Waitaki, anchored by the footsteps of Roko Marae Roa.

We carry the wisdom of our tīpuna and the aspirations of our mokopuna as the first people of Te Waipounamu.

Together, we move confidently and collectively into the future as an independent iwi, creating an environment where our people and culture can thrive.

Explore

The Waitaha journey from

Te-Pātunui-o-āio to Waitaha

Te-Pātunui-o-āio: Beyond Hawaiki

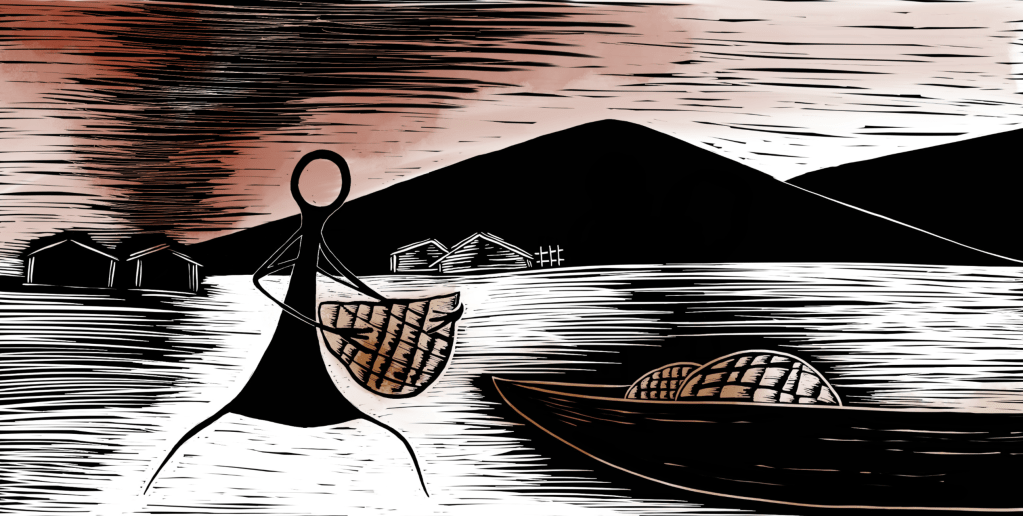

Waitaha trace their origins to Te-Pātunui-o-āio—a peaceful and sacred homeland beyond Hawaiki-pāmamao.

It is from this place that our ancestors began their journey across the great ocean in search of a new life.

The Journey of Uruao

Our eponymous ancestor Rākaihautū led the voyage aboard the waka Uruao, with a large crew including members of three other iwi.

With his toki (adze) and sacred incantations, he is said to have opened a path through the waves, guiding the waka safely to Aotearoa.

Arrival & Exploration

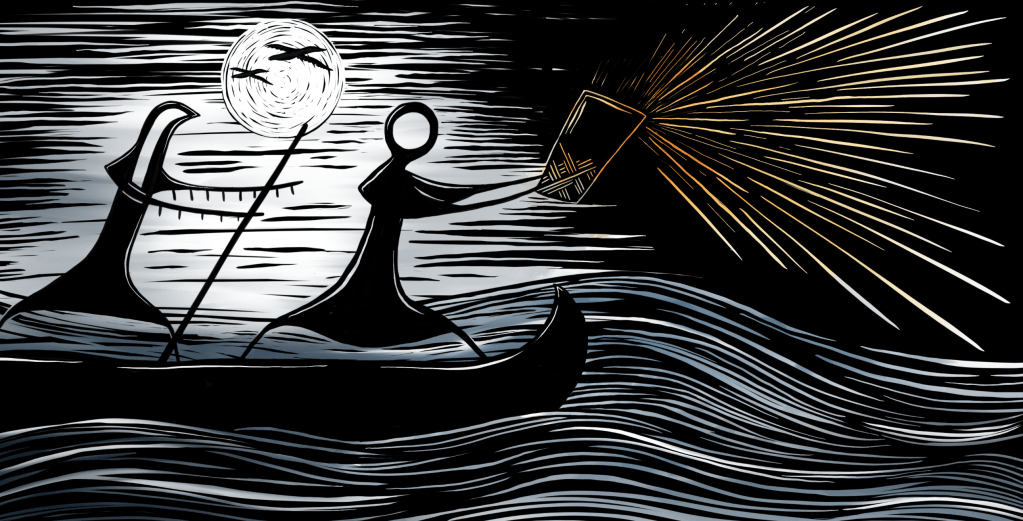

The Uruao first landed at Te Rerenga Wairua | Cape Reinga, stopped at Ahuriri | Napier, then voyaged south to Whakatū | Nelson, the gateway to Te Waipounamu | South Island. It was here, Waitaha lit the first fires of occupation (ahi kā), symbolising our permanent connection to the whenua.

From Whakatū, Rākaihautū explored inland along the east side of Kā Tiritiri o te Moana | Southern Alps, south to Ōtākou | Otago and well into Waitaha | Canterbury. His son Rakihouia remained on the Uruao and travelled by sea down the east coast.

Shaping the Land and Lighting the Fires

Using his sacred kō, Tūwhakarōria, Rākaihautū carved out the great lakes including Wānaka, Wakatipu, Takapō, and Pūkaki, establishing our ancestral land rights and leaving a permanent mark on the landscape.

Huruhuru Manu

Our first settlement, Huruhuru Manu, lay by the Waitaki River mouth.

Lifestyle

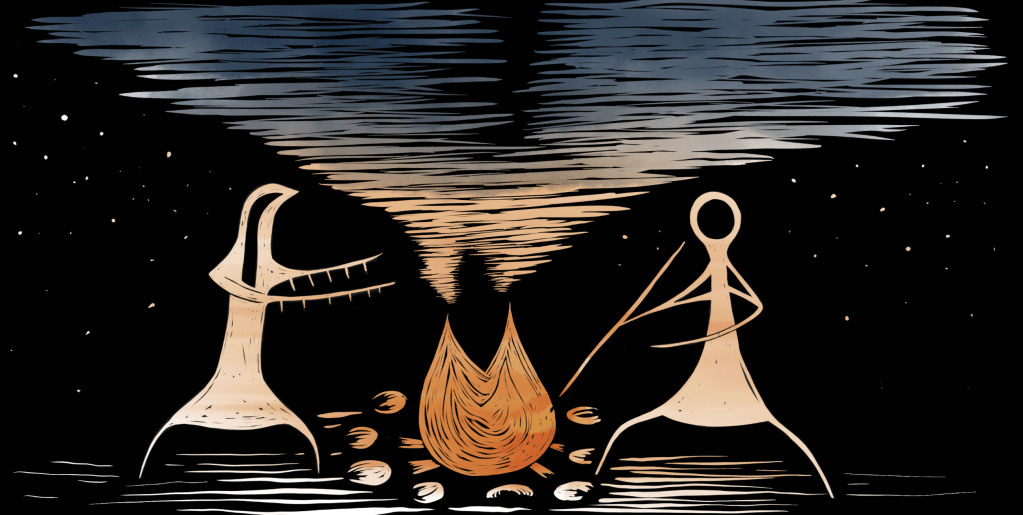

Waitaha spent months travelling across the motu | island in search of kai | food, clothing materials, and tools and had a mix of permanent and seasonal occupation sites. The mōkihi – made from raupō and harakeke – was essential for transportation along our awa | rivers.

Banks Peninsula, known as Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū | the storehouse of Rākaihautū, was teeming with kai like tuna | eel and pātiki | flounder. We travelled the high country seasonally to hunt moa and other birds, dig aruhe | fern root and raupō | bulrush root, and quarry stone for tools.

Prosperity, Knowledge, and Kaitiakitaka

We were peaceful and industrious, skilled in karakia and astronomy, using limestone caves throughout the motu | island for shelter and for teaching, creating drawings on rock faces with fat and charcoal (much of this rock art remains today).

We traded moa meat, kāuru | stem of the tī kōuka, and taramea oil for kūmara, whāriki, and waka from northern iwi. We promoted peace amongst the other iwi that migrated to Te Waipounamu including Kāti Mamoe around 1550AD and Ngāi Tahu around 1685AD.

Waitaha, as ahi kā and kaitiaki, continued to uphold the mauri of land and water, practising sustainable harvest and spiritual rituals to maintain balance with Papatūānuku.

Archaeology and Rediscovery

Despite the strengthening and spread of other iwi in Te Waipounamu and the settling of Pākehā, the Waitaha people remain. Our legacy is evident across the landscape in our names, our rock art, and our taoka | sacred artefacts.

The tohuka | prophet, Te Maihāroa (1800 – 1886), established a wharekura | school at Korotuaheka (on the banks of the Waitaki, close to Huruhuru Manu) teaching mātauraka Waitaha | traditional Waitaha knowledge, whakapapa | genealogy, astronomy, tikaka Waitaha | ways of Waitaha, and peaceful resistance to breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. He also established a wharekura at Arowhenua called Te Anarewa.

As ariki tauaroa | paramount chief and a staunch advocate for indigenous rights, Te Maihāroa lobbied both the New Zealand Government and the Queen of England to assert his ahi kā roa, uninterrupted occupation of his ancestral lands. In 1877, he led Te Heke, a peaceful protest to physically occupy the unsold lands in central Te Waipounamu, often referred to as ‘the hole in the middle’. Here, at Te Aomarama (Ōmarama), he established a wharekura named Te Waka-āhua-a-raki. Te Maihāroa and his followers were evicted from these lands in the winter of 1879.

They returned to Korotuaheka.

Endurance, Te Maihāroa, and Peaceful Resistance

Waitaha carry the vision of Rākaihautū and Te Maihāroa as ahi kā and kaitiaki.

Though Huruhuru Manu was left quiet, our presence endured. Beneath the soil lay evidence of the ingenuity of our tīpuna — earth ovens, moa bones, stone tools — revealing a rich life of trade, technology, and movement across islands. These taoka tell the story of a people deeply connected to the whenua. Today, they form a nationally significant collection, helping us remember, honour, and pass on the knowledge of those who came before.

Waitaha whānau continue to uphold rakatirataka (self-determination), protect the mauri of land and water, and keep alive the flame of identity and ancestral connection.

We have a place to gather and share these stories: Ko Awearaki te Whare Tīpuna, located in Pareora, named for Awearaki, son of Rakihouia and Te Ao Tapu-iti. This whare is a home for our whakapapa, mātauraka, and wānaka, nurtured by the efforts of many whānau.